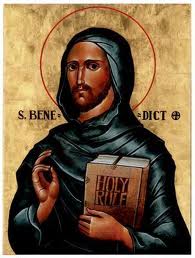

Rule of St Benedict

The Rule of St Benedict (fl. 6th century) is a book of precepts written by St. Benedict of Nursia for monks living in community under the authority of an abbot. Since about the 7th century it has also been adopted by communities of women. During the 1500 years of its existence, it has become the leading guide in Western Christianity for monastic living in community, in Orthodoxy, Catholicism and (since the time of the Reformation) in the Anglican and Protestant traditions.

for monks living in community under the authority of an abbot. Since about the 7th century it has also been adopted by communities of women. During the 1500 years of its existence, it has become the leading guide in Western Christianity for monastic living in community, in Orthodoxy, Catholicism and (since the time of the Reformation) in the Anglican and Protestant traditions.

The spirit of St Benedict’s Rule is summed up in the motto of the Benedictine Confederation: pax (“peace”) and the traditional ora et labora (“pray and work”).

Compared to other precepts, the Rule provides a moderate path between individual zeal and formulaic institutionalism; because of this middle ground it has been widely popular. Benedict’s concerns were the needs of monks in a community environment: namely, to establish due order, to foster an understanding of the relational nature of human beings, and to provide a spiritual father to support and strengthen the individual’s ascetic effort and the spiritual growth that is required for the fulfillment of the human vocation, theosis.

The Rule of St Benedict has been used by Benedictines for fifteen centuries, and thus St. Benedict is sometimes regarded as the founder of Western monasticism. There is, however, no evidence to suggest that Benedict intended to found a religious order. Not until the later Middle Ages is there mention of an “Order of St Benedict”. His Rule is written as a guide for individual, autonomous communities; and to this day all Benedictine Houses (and the Congregations in which they have associated themselves) remain self-governing. Advantages seen in retaining this unique Benedictine emphasis on autonomy include cultivating models of tightly bonded communities and contemplative life-styles. Disadvantages are said to comprise geographical isolation from important projects in adjacent communities in the name of a literalist interpretation of autonomy. Other losses are said to include inefficiency and lack of mobility in the service of others, and insufficient appeal to potential members feeling called to such service.

Origins

Christian monasticism first appeared in the Eastern Roman Empire a few generations before Benedict of Nursia, in the Egyptian desert. Under the spiritual inspiration of Saint Anthony the Great (251–356), ascetic monks led by Saint Pachomius (286–346) formed the first Christian monastic communities under what became known as an Abba (Aramaic for “Father”, from which the term Abbot originates).

Within a generation, both solitary and communal monasticism became very popular and spread outside of Egypt, first to Palestine and the Judean Desert and thence to Syria and North Africa. Saint Basil of Caesarea codified the precepts for these eastern monasteries in his Ascetic Rule, or Ascetica, which is still used today in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

In the West in about the year 500, Benedict became so upset by the immorality of society in Rome that he gave up his studies there and chose the life of an ascetic monk in the pursuit of personal holiness, living as a hermit in a cave near the rugged region of Subiaco. In time, setting a shining example with his zeal, he began to attract disciples. After considerable initial struggles with his first community at Subiaco, he eventually founded the monastery of Monte Cassino, where he wrote his Rule in about 530.[citation needed]

In the West in about the year 500, Benedict became so upset by the immorality of society in Rome that he gave up his studies there and chose the life of an ascetic monk in the pursuit of personal holiness, living as a hermit in a cave near the rugged region of Subiaco. In time, setting a shining example with his zeal, he began to attract disciples. After considerable initial struggles with his first community at Subiaco, he eventually founded the monastery of Monte Cassino, where he wrote his Rule in about 530.[citation needed]

In chapter 73 St Benedict commends the Rule of St Basil and alludes to further authorities, obviously. He was probably aware of the Rule written by (or attributed to) Pachomius; and his Rule also shows influence by the Rules of Augustine of Hippo and Saint John Cassian. Benedict’s greatest debt, however, may be to the anonymous Rule of the Master, which he seems to have radically excised, expanded, revised and corrected in the light of his own considerable experience and insight. [1]

Overview of the Rule

The Rule opens with a prologue or hortatory preface, in which St Benedict sets forth the main principles of the religious life, viz.: the renunciation of one’s own will and arming oneself “with the strong and noble weapons of obedience” under the banner of “the true King, Christ the Lord” (Prol. 3). He proposes to establish a “school for the Lord’s service” (Prol. 45) in which the way to salvation (Prol. 48) shall be taught, so that by persevering in the monastery till death his disciples may “through patience share in the passion of Christ that [they] may deserve also to share in his Kingdom” (Prol. 50, passionibus Christi per patientiam participemur, ut et regno eius mereamur esse consortes; note: Latin passionibus and patientiam have the same root, cf. Fry, RB 1980, p. 167).

- In Chapter 1 are defined the four kinds of monks: (1) Cenobites, namely those “in a monastery, where they serve under a rule and an abbot”; (2) Anchorites, or hermits, those who, after long successful training in a monastery, are now coping single-handedly, with only God for their help; (3) Sarabaites, living by twos and threes together or even alone, with no experience, rule and superior, and thus a law unto themselves; and (4) Gyrovagues, wandering from one monastery to another, being slaves to their own wills and appetites. It is for the first of these kinds of monks, the cenobites, as the “strongest kind” (fortissimum genus; arguably “numerically stronger”, cf. Fry, RB 1980, p. 171), that the Rule is written.

- Chapter 2 describes the necessary qualifications of an abbot and forbids him to make distinction of persons in the monastery except for particular merit, warning him at the same time that he will be answerable for the salvation of the souls committed to his care.

- Chapter 3 ordains the calling of the brethren to council upon all affairs of importance to the community.

- Chapter 4 gives a list of 73 “tools for good work”/”tools of the spiritual craft” that are to be used in the “workshop” that is “the enclosure of the monastery and the stability in the community”. They are essentially the duties of every Christian and are mainly Scriptural either in letter or in spirit.

- Chapter 5 prescribes prompt, ungrudging, and absolute obedience to the superior in all things lawful, “unhesitating obedience” being called the first degree, or step, of humility.

- Chapter 6 deals with silence, recommending moderation in the use of speech, but by no means prohibiting profitable or necessary conversation.

- Chapter 7 treats of humility, which virtue is divided into twelve degrees or steps in the ladder that leads to heaven. They are: (1) fear of God; (2) repression of self-will; (3) submission of the will to superiors for the love of God; (4) obedience in difficult, contrary or even unjust conditions; (5) confession of sinful thoughts and secret wrong-doings; (6) contentment with the lowest and most menial treatment and acknowledgment of being “a poor and worthless workman” in the given task; (7) honest acknowledgement of one’s inferiority to all others; (8) being guided only by the monastery’s common rule and the example of the superiors; (9) speaking only when asked a question; (10) stifling ready laughter; (11) seriousness, modesty, brevity and reasonableness in speech and a calm voice; (12) outward manifestation of the interior humility.

- Chapters 9-19 are occupied with the regulation of the Divine Office, the opus Dei to which “nothing is to be preferred”, namely the canonical hours, seven of the day and one of the night. Detailed arrangements are made as to the number of Psalms, etc., to be recited in winter and summer, on Sundays, weekdays, Holy Days, and at other times.

- Chapter 19 emphasizes the reverence owed to the omnipresence of God.

- Chapter 20 directs that prayer be made with heartfelt compunction rather than many words, and prolonged only under the inspiration of divine grace, but in community always short and terminated at the sign given by the superior.

- Chapter 21 provides for the appointment of Deans over every ten monks, and prescribes the manner in which they are to be chosen.

- Chapter 22 regulates all matters relating to the dormitory, as, for example, that each monk is to have a separate bed and is to sleep in his habit, so as to be ready to rise without delay [for early Vigils], and that a light shall burn in the dormitory throughout the night.

- Chapter 23-29 deal with contumacy, disobedience, pride and other grave faults for which a graduated scale of punishments is provided: first, private admonition; next, public reproof; then separation from the brethren at meals and elsewhere; and finally excommunication (or in the case of those lacking understanding of what this means, corporal punishment instead). The abbot, like a wise physician and good shepherd, is to arrange for mature and wise members of the community to counsel wayward members in private, while all offer prayers in support, so that in compassion those who show themselves sick by their conduct may, in compassion, be carried back to the flock. After frequent reproofs and maybe even excommunication has proved unavailing, corporal punishment is to be dispensed. If every effort to help a wayward member reform has failed, the abbot and community are to pray for him, “so that the Lord, who can do all things, may bring about the ‘health’ of the ‘sick’ brother”. If this does not “heal” him, the abbot is to send him away to protect the community.

- Chapter 30 directs that if a wayward brother leaves the monastery, he must be received again, if he promises to make amends; but if he leaves again, and again, after the third time all return is finally barred.

- Chapter 31 and 32 order the appointment of a cellerar and other officials, to take charge of the various goods of the monastery, which are to be treated with as much care as the consecrated vessels of the altar.

- Chapter 33 forbids the private possession of anything without the leave of the abbot, who is, however, bound to supply all necessities.

- Chapter 34 prescribes a just distribution of such things.

- Chapter 35 arranges for the service in the kitchen by all monks in turn.

- Chapter 36 and 37 order due care for the sick, the old, and the young. They are to have certain dispensations from the strict Rule, chiefly in the matter of food.

- Chapter 38 prescribes reading aloud during meals, which duty is to be performed by such of the brethren, week by week, as can do so with edification to the rest. Signs are to be used for whatever may be wanted at meals, so that no voice shall interrupt that of the reader. The reader is to have his meal with the servers after the rest have finished, but he is allowed a little food beforehand in order to lessen the fatigue of reading.

- Chapter 39 and 40 regulate the quantity and quality of the food. Two meals a day are allowed and two dishes of cooked food at each. A pound of bread also and a hemina (probably about half a pint) of wine for each monk. Flesh-meat is prohibited except for the sick and the weak, and it is always within the abbot’s power to increase the daily allowance when he sees fit.

- Chapter 41 prescribes the hours of the meals, which are to vary according to the time of year.

- Chapter 42 enjoins the reading of the “Conferences” of Cassian or some other edifying book in the evening before Compline and orders that after Compline the strictest silence shall be observed until the following morning.

- Chapters 43-46 relate to minor faults, such as coming late to prayer or meals, and impose various penalties for such transgressions.

- Chapter 47 enjoins on the abbot the duty of calling the brethren to the “world of God” in choir, and of appointing those who are to chant or read.

- Chapter 48 emphasizes the importance of manual labour and arranges time to be devoted to it daily. This varies according to the season, but is apparently never less than about five hours a day. The times at which the lesser of the “day-hours” (Prime, Terce, Sext, and None) are to be recited control the hours of labour somewhat, and the abbot is instructed not only to see that all work, but also that the employments of each are suited to their respective capacities.

- Chapter 49 treats of the observance of Lent, and recommends some voluntary self-denial for that season, with the abbot’s sanction.

- Chapters 50 and 51 contain rules for monks who are working in the fields or traveling. They are directed to join in spirit, as far as possible, with their brethren in the monastery at the regular hours of prayers.

- Chapter 52 commands that the oratory be used for purposes of devotion only.

- Chapter 53 is concerned with the treatment of guests, who are to be received “as Christ Himself”. This Benedictine hospitality is a feature which has in all ages been characteristic of the order. The guests are to be met with due courtesy by the abbot or his deputy, and during their stay they are to be under the special protection of a monk appointed for the purpose, but they are not to associate with the rest of the community except by special permission.

- Chapter 54 forbids the monks to receive letters or gifts without the abbot’s leave.

- Chapter 55 regulates the clothing of the monks. It is to be sufficient in both quantity and quality and to be suited to the climate and locality, according to the discretion of the abbot, but at the same time it must be as plain and cheap as is consistent with due economy. Each monk is to have a change of garments, to allow for washing, and when traveling shall be supplied with clothes of rather better quality. The old habits are to be put aside for the poor.

- Chapter 56 directs that the abbot shall take his meals with the guests.

- Chapter 57 enjoins humility on the craftsmen of the monastery, and if their work is for sale, it shall be rather below than above the current trade price.

- Chapter 58 lays down rules for the admission of new members, which is not to be made too easy. These matters have since been regulated by the Church, but in the main St. Benedict’s outline is adhered to. The postulant first spends a short time as a guest; then he is admitted to the novitiate, where under the care of a novice-master, his vocation is severely tested; during this time he is always free to depart. If after twelve months’ probation, he still perseveres, he may be admitted to promise before the whole community stabilitate sua et conversatione morum suorum et oboedientia (usually translated “stability, conversion of manners, and obedience”, or “stability, fidelity to monastic life, and obedience”, and regarded as a single vow), whereby he binds himself for life to the monastery of his profession.

- Chapter 59 allows the admission of boys to the monastery under certain conditions.

- Chapter 60 regulates the position of priests who may desire to join the community. They are charged with setting an example of humility to all, and can only exercise their priestly functions by permission of the abbot.

- Chapter 61 provides for the reception of strange monks as guests, and for their admission if desirous of joining the community.

- Chapter 62 lays down that precedence in the community shall be determined by the date of admission, merit of life, or the appointment of the abbot.

- Chapter 64 orders that the abbot be elected by his monks and that he be chosen for his charity, zeal, and discretion.

- Chapter 65 allows the appointment of a provost, or prior, if need be, but warns that this provost is to be entirely subject to the abbot and may be admonished, deposed, or expelled for misconduct.

- Chapter 66 provides for the appointment of a porter, and recommends that each monastery should be, if possible, self-contained, so as to avoid the need of intercourse with the outer world.

- Chapter 67 gives instruction as to the behavior of a monk who is sent on a journey.

- Chapter 68 orders that all shall cheerfully attempt to do whatever is commanded them, however hard it may seem.

- Chapter 69 forbids the monks from defending one another.

- Chapter 70 prohibits them from striking one another.

- Chapter 71 encourages the brethren to be obedient not only to the abbot and his officials, but also to one another.

- Chapter 72 is a brief exhortation to zeal and fraternal charity

- Chapter 73 is an epilogue declaring that this Rule is not offered as an ideal of perfection, but merely as a means towards godliness and is intended chiefly for beginners in the spiritual life.

Secular significance

Beyond its religious influences, the Rule of St Benedict is one of the most important written works in the shaping of Western society, embodying, as it does, the idea of a written constitution, authority limited by law and under the law, and the right of the ruled to review the legality of the actions of their rulers. It also incorporated a degree of democracy in a non-democratic society.

Outline of the Benedictine life

St Benedict’s model for the monastic life was the family, with the abbot as father and all the monks as brothers. Priesthood was not initially an important part of Benedictine monasticism – monks used the services of their local priest. Because of this, almost all the Rule is applicable to communities of women under the authority of an abbess.

St Benedict’s Rule organises the monastic day into regular periods of communal and private prayer, sleep, spiritual reading, and manual labour – ut in omnibus glorificetur Deus, “that in all [things] God may be glorified” (cf. Rule ch. 57.9). In later centuries, intellectual work and teaching took the place of farming, crafts, or other forms of manual labour for many – if not most – Benedictines.

Traditionally, the daily life of the Benedictine revolved around the eight canonical hours. The monastic timetable or Horarium would begin at midnight with the service, or “office”, of Matins (today also called the Office of Readings), followed by the morning office of Lauds at 3am. Before the advent of wax candles in the 14th century, this office was said in the dark or with minimal lighting; and monks were expected to memorize everything. These services could be very long, sometimes lasting till dawn, but usually consisted of a chant, three antiphons, three psalms, and three lessons, along with celebrations of any local saints’ days. Afterwards the monks would retire for a few hours of sleep and then rise at 6am to wash and attend the office of Prime. They then gathered in Chapter to receive instructions for the day and to attend to any judicial business. Then came private Mass or spiritual reading or work until 9am when the office of Terce was said, and then High Mass. At noon came the office of Sext and the midday meal. After a brief period of communal recreation, the monk could retire to rest until the office of None at 3pm. This was followed by farming and housekeeping work until after twilight, the evening prayer of Vespers at 6pm, then the night prayer of Compline at 9pm, and off to blessed bed before beginning the cycle again. In modern times, this timetable is often changed to accommodate any apostolate outside the monastic enclosure (e.g. the running of a school or parish).

Many Benedictine Houses have a number of Oblates (secular) who are affiliated with them in prayer, having made a formal private promise (usually renewed annually) to follow the Rule of St Benedict in their private life as closely as their individual circumstances and prior commitments permit.

In recent years discussions have occasionally been held concerning the applicability of the principles and spirit of the Rule of St Benedict to the secular working environment.

Reforms

During the more than 1500 years of their existence, the Benedictines have not been immune to periods of laxity and decline, often following periods of greater prosperity and an attendant relaxing of discipline. In such times, dynamic Benedictines have often led reform movements to return to a stricter observance of both the letter and spirit of the Rule of St Benedict, at least as they understood it. Examples include the Camaldolese, the Cistercians, the Trappists (a reform of the Cistercians), and the Sylvestrines. At the heart of reform movements, past and present, lie hermeneutical questions about what fidelity to tradition means. For example are sixth-century objectives, like blending in with contemporary dress or providing service to visitors, better served or compromised by retaining sixth-century clothing or by insisting that service excludes formal educational enterprises?

Urban legend concerning the Rule of St Benedict

A popular urban legend claims that the Rule of St Benedict (when translated into English), contains the following (or similar) passage:

- If any pilgrim shall come from distant parts with wish to dwell in the monastery, and will be content with the customs of the place, and does not by his lavishness disturb the monastery but is simply content, he shall be received for as long as he wishes.

- If, indeed, he shall find fault with anything, and shall expose the matter reasonably and with the humility of charity, the Abbott shall discuss it with him prudently lest perchance God hath sent him for this very thing.

- But, if he shall have been found contumacious during his sojourn in the monastery, then it shall be said to him, firmly, that he must depart. If he will not go, let two stout monks, in the name of God, explain the matter to him.

Though much of the supposed passage is condensed from Chapter 61 (LXI) of the Rule, the Rule of St Benedict contains no language corresponding to the last sentence about “two stout monks”; though it is a popular myth that it does, with several reputable publications (and more than one church, and at least one Benedictine organization) repeating and propagating the error. At least one of the sources cited attributes the passage to a mythical Chapter 74; the Rule of St Benedict contains only 73 chapters. [2]. [3] [4] [5]

An early source for the quotation is the University of California, Berkeley faculty club, which has, for years, posted the above passage on its bulletin board in Gothic script. (There, the notice was not attributed to St Benedict). [6].

References

This article incorporates text from the public-domain Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913.

- R. W. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages. Pelican, 1970

- Henry Mayr-Harting, The Venerable Bede, the Rule of St Benedict, and Social Class. Jarrow Lecture 1976; Jarrow: Rector of Jarrow, 1976. ISBN 0903495031

- Christopher Derrick, The Rule of Peace: St. Benedict and the European Future. Still River, Mass.: St. Bede’s Publications. 2002. ISBN 978-0932506016

External links

- An Introduction to the Rule by Jerome Theisen, former Abbot Primate of the Benedictine Confederation

- The Holy Rule of St. Benedict, translated by Rev. Boniface Verheyen, OSB. — Online edition provided by St. Benedict’s Abbey, Atchison, Kansas.

- A brief introduction on the history and spirit of the Benedictine life, as well as the English text of RB 1980 – The Rule of St Benedict in Latin and English with Notes, Timothy Fry OSB (ed.), Collegeville 1981 (Prologue and cch. 1-7 only, with a commentary by Abbot Philip Lawrence OSB) From the website of the Monastery of Christ in the Desert.

- The Rule of St. Benedict in Latin